âA Tide of Dreamsâ tells story of Bryantâs early days

EDITOR’S NOTE: Carey Henry Keefe’s “A Tide of Dreams: The Untold Backstory of Coaches Paul ‘Bear’ Bryant, Carney Laslie and Frank Moseley” was published last October by Koehler Books. As the title implies, it tells a story that was largely unknown previously, Bryant’s journey to becoming an all-time football icon and the close friendships with key assistant coaches that helped forge that path.

Keefe — who was Laslie’s granddaughter — recently spoke with AL.com about the book, which has been released in paperback, just in time for Father’s Day. The following is an edited Q&A from that conversation.

Q: I guess the question every author gets when they write a book, especially on something that’s an unknown subject to a degree, is what led you to this story and what made you think it would make a compelling book?

A: “Well, I’ve been thinking about it for a very long time. I actually went to college wanting to be a writer. And so I’ve always been on the lookout for a good story. But I changed my direction, my career path and went into business. But I went to Frank Moseley’s funeral (in 1979), and I thought of all of those things that I had heard and learned. I thought, I needed to tell their story, because it would be long gone. … I had written a novel, but I was looking for more material. But then (Laslie’s lost Alabama national championship) ring was found, which I talk about in the book. And I thought, you know, this is a really good story. But some things are not a book, but just more of an essay or short story. We never went back to Alabama after my grandmother died in 1972, but as my mother was aging, I realized I needed to write the story. I did a lot of research, talked to a lot of different people before I started the writing. And I wanted to verify a few things with Paul Bryant Jr., so I called him early on before the project, and then went down to actually meet with him. And he was very gracious. And I said, ‘I’m going to write their story and it would be great if you could help facilitate that.’ And he was very willing to do that. He said ‘no one was closer to my dad than Uncle Carney.’ So on we went, and the more I got into it, the more I saw that it was very intriguing, very interesting story, even if it’s not really a book about football.”

Q: You make no bones about the fact you’re not really a football person. But there are so many universal things in the story, not only the drama of the military and World War II, and what that did to the country and their lives and all that, and the friendship between Bryant, Laslie and Moseley. That’s the core of the whole story, isn’t it?

A: “Yes, I don’t think that’s modeled enough in our culture. And in this generation, I think that we’ve kind of lost that idea that successful ventures often take a team of people. There always has to be the guy that is the front guy and that was Bryant. They had a very unique collaborating, working relationship and friendship. I think that because it was rooted in their early days, their college friendship, but then that was sort of what war brotherhood really does — solidify those connections. And that’s a big part of the story. An unknown part of the story was the (Navy) pre-flight program that started in World War II. A lot of coaches who were in that program went on to coach powerhouse programs in the SEC and the Big Ten during those post-war years. But Bryant’s legacy certainly at Alabama was that he became the face college football for that generation, those golden years. So that’s when I knew it was a good story.”

Q: Were you intimidated at all trying to tell football stories not really being a sports writer, particularly on a subject like Bryant, who has had literally hundreds of books written about him?

A: “I read a few of them. And I talked to a few writers that had covered Bryant in his later years. (Laslie) was dead by then, but they said ‘all the old coaches talked about Carney’ but nobody (younger) really knew who he was. People did not remember him because he had died in 1970. And he was kind of a footnote, but they realized he was somebody important. But by the 1980s, there was just nobody left that knew the whole story going back to the 1940s. Someone asked me, ‘does it bother you that your grandfather isn’t profiled more in the Bryant Museum?’ And I said ‘no, my grandfather wouldn’t have wanted that anyway.’ But I think telling (Laslie’s) story adds another dimension to who Paul Bryant was that’s missing from a lot of books about him, how his career really shaped up. It’s kind of the behind-the-scenes story. To your question, was it intimidating? In one part, yes. And another part, no. Some of the accounts were incorrectly understood. So it gave me a little bit of a gave me confidence, o know I was pursuing something with it was worthwhile, not really out to correct the record, so to speak, but just to say, what is out there is only in-part true. Like most things, there’s another side. It’s like looking at a house and seeing it from the front part. But when you go to the back of the house and look at it, you can often see the house in a totally different light and appreciate it in a different way.”

Q: Although Moseley eventually went off to become head coach at VPI (now Virginia Tech), your grandfather never did that. He seemed happy to stay as an assistant. Do you think he and other realized, ‘hey, Bryant’s the star and we’re OK with that?’

A: “Yes, their goal, their aspiration, was for the three of them to be successful together. But it’s always a two-sided coin. Frank realized at a certain he needed to go back to Virginia. I think I turned that he chose the love of his life over the love of football. But my grandfather had plenty of opportunities to be a head coach, but he did not want to be a head coach. In his early years, he coached in high school. But I think he preferred to be a coach’s coach. And he knew that Bryant had ‘it.’ (Laslie) had the ability to connect with the players. Bryant said that in his autobiography as well, that he never knew anybody who could motivate a player like Carney Laslie.’ But the same was said of (Bryant). My grandfather felt the same way about him. They both had that passion to win, and they both had the core values. They knew they could win national championships together.”

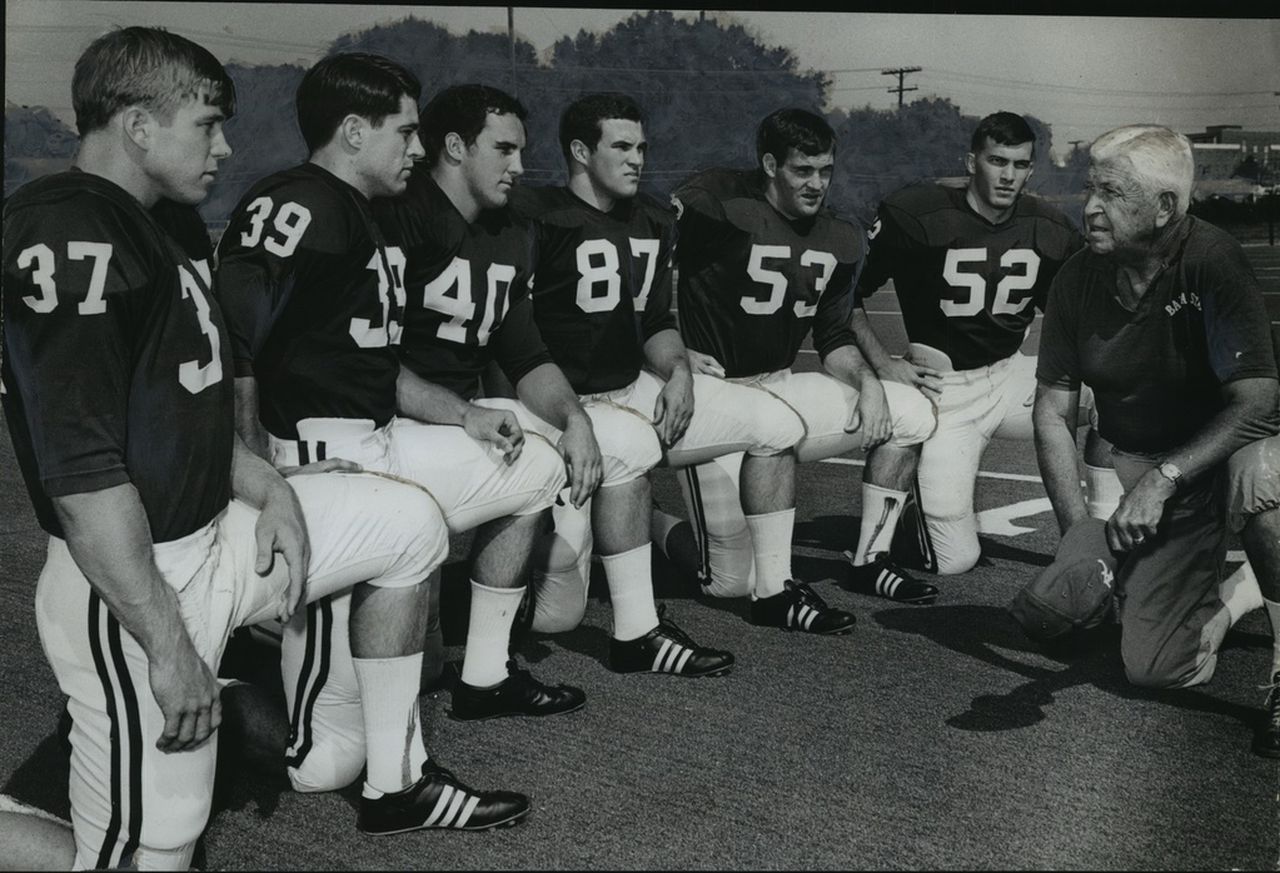

Alabama assistant coach Carney Laslie is shown with several Crimson Tide players in 1968. (University of Alabama photo)The Birmingham News

Q: (World War II) is obviously such a huge part of not only your book, but the life everybody who grew up in that generation. How do you think that changed or affected them, not only as football coaches, but as people for the rest of their lives?

A: “I think they learned about the collaborative nature and the partnership that it took for so many people to win the war, and how it could be applied to football and to life in general. So many people worked so well together during the war, and I think that’s something that’s lost nowadays. The people that came out of World War II realized how sports really was a breeding ground for patriotism. Love of country really came out of love for your alma mater, your school, your state. They wanted to bring their schools back to the glory days the same way they and so many other had done with the country during the war. Love of country, love of God, love of family, they firmly believed in those ideals. You can be fighting your ‘enemy,’ say Alabama vs. LSU, but at the end of the day, we’re all Americans. But the war definitely changed them. It made them realize what they owed to the people who lost their lives, like Jimmy Walker, who was one of the four (friends) and who was killed in World War II. I think (the war and his death) framed a lot of their desire to do well. For those for those men that they coached with, but also remembering the players that they lost that they trained.”

Q: You also write about the North Carolina Pre-Flight program during World War II, which hasn’t been detailed in many other places. How did you happen upon that material?

A: “The publisher had the manuscript, but they hadn’t started editing yet. And I really felt strongly that the glaring void was details about the pre-flight program and what went on there. I found a few articles online, but they were written by the military and didn’t go into much detail. When I was researching a cover, I ran across a book called ‘The Cloudbuster Nine,’ which is about Ted Williams and his time as a player on the pre-flight baseball team. And I immediately ordered it. As I was reading it, I thought ‘this is the information I’ve been looking for.’ So I emailed the author (Anne R. Keene) and we talked for two hours. And at the end of that time, she told me ‘I’m sending you all my research,’ which she had done in the University of North Carolina archives. It was a treasure trove of information. I really owe here a great deal of gratitude.”

Q: Speaking of the war, you go into detail on one of the great ‘what ifs’ in Bryant’s career, which is that he very likely would have taken the job at Arkansas (his home state school) if not for the war. How would that have changed their lives and careers going forward, do you think?

A: “It was definitely one of those all-time ‘roads not taken’ in football. (Bryant, Laslie and Walker) all had ties to Arkansas. But (Bryant) would have gotten it done at Arkansas. It would have been a great, great program. And who knows what would have happened to Alabama? Bryant might never have left Arkansas, though I think Hank Crisp might have figured out a way to get him back to Tuscaloosa. … And of course, they played Arkansas in the Sugar Bowl at the end of the 1961 season, after they’d won their first national championship at Alabama, which I touch on at the end of the book.”

Creg Stephenson is a sports writer for AL.com who has written about college football and other sports for more than 25 years. Follow him on Twitter at @CregStephenson or email him at [email protected].